When ‘kindness’ hurts and excludes

How storytellers can recognise and unlearn “benevolent ableism”; StoryLab updates; media recommendations

Dear Readers,

The past few weeks were hectic, filled with the usual anxieties that come with building something new. But most of that disappeared once Zainab and I met the inaugural cohort of the StoryLab mentorship programme. Listening to the participants’ ideas and brainstorming together on how to strengthen those ideas in the first session was energising.

When we first opened applications, we didn’t expect the response we received. Thirty journalists, writers, and storytellers with disabilities from across the world applied. We could only include four this first time, with the hope of having more in future cohorts.

We were pleasantly surprised, and moved even, to see so many applicants striving to bring about change in their own ways. As the applications indicated, many are not publicly open about their disabilities, yet they continue their work, often quietly and courageously.

This only confirmed what a big gap there is when it comes to disabled storytellers who need opportunities to connect and learn with each other and build the confidence to be able to bring their whole selves into their work.

I’d found the first evidence of this gap during my research on disability representation in Indian newsrooms three years ago. Seeing it reflected globally only reinforces how urgent it is to create these spaces.

My research also indicated the difference it could make if we strengthened these networks by building supportive spaces where journalists with disabilities can share their experiences, express their identities, and discuss their ideas freely.

We want journalism that can hold space for our perspectives, and for us, because – believe it or not – disabled people form 16% (and growing) of the world’s population. Journalism needs disabled people to truly reflect the society it serves.

Another heartening development was when several journalists wrote in, offering to share their skills and mentor the programme, a gesture that truly means so much to us.

Reframing Disability is creating a database of journalism mentors, and I welcome your messages if you’re interested. We couldn’t be more excited for the journey ahead with StoryLab and would love for you to join us. Hit reply. Let’s chat.

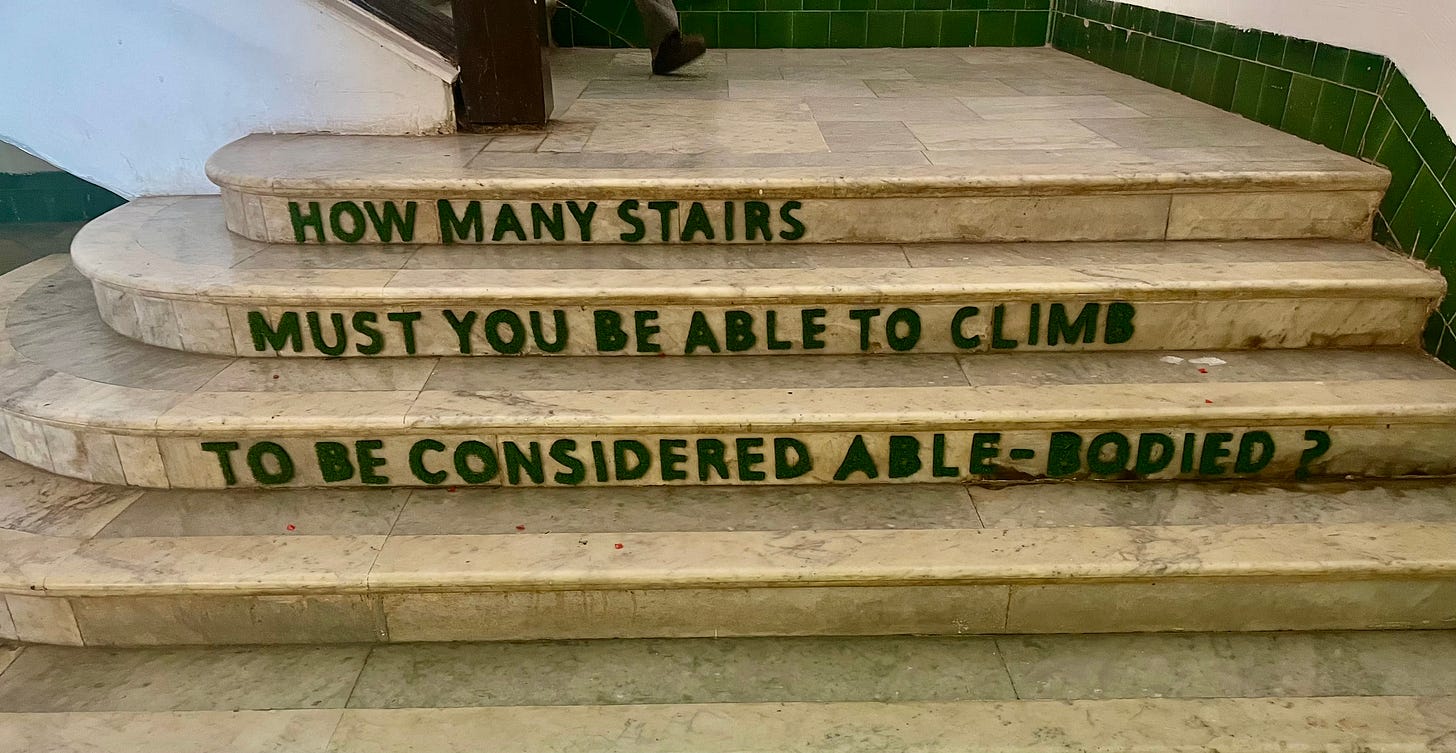

[ID: Marble steps at the Old GMC Complex in Panjim, Goa, with green embossed words in uppercase: How many stairs must you be able to climb to be considered able-bodied? Photographed by me at the Serendipity Arts Festival in December 2024]

[Video Description and caption: Jibin Joy, a young Indian man dressed in black trousers and shirt, and Jyothika Jayakrishnan, an Indian woman in a long blue top sign the piece on benevolent ableism. Both are Deaf interpreters and Indian Sign Language fellows at the ISL Interpreters Fellowship at Hear A Million, a project by Enable India in Bengaluru.]

Today’s piece is about “benevolent ableism” and its harms. Simply put, “benevolent ableism is when individuals, typically with good intentions, set apart people with disabilities (often unintentionally) by trying to help, but in doing so, feed into stigmas that people with disabilities aren’t as “able” as everyone else.”

Contributed by Anugya Srivastava, whose passion for disability inclusion I’ve long admired! Read on and let us know your thoughts in comments!

“Celebrate our achievements in the same way you would for anyone else, not as miracles, but as milestones”

By Anugya Srivastava

When Ankur Kankonkar lost his sight as a young man, he assumed at least his friendships would remain unchanged. But soon, he noticed invitations to social outings from some friends stopped coming, assuming he wouldn’t be able to navigate restaurants or busy streets anymore and feel uncomfortable in the company of his non-disabled friends. “They didn’t ask. They decided for me,” recalls Ankur, the CEO of AnklyticX, a tech and management consulting company based in Goa.

Puneet Singh Singhal, who lives with stammering, a speech disability, recalls moments that continue to sting him. “In meetings, I’ve had people interrupt or finish my sentences, assuming they’re ‘helping’ me. It’s humiliating. It sends a message: your voice doesn’t matter; your pace isn’t worth waiting for.” It’s ironic because Puneet is an acclaimed climate and disability advocate and co-founder of the identity and empowerment organisation, Billion Strong.

Well-intentioned actions and attitudes – the kind Ankur and Puneet have endured – can reinforce exclusion just as much as the more blatant forms of ableism society often overlooks.

The deeper harm of these actions, Puneet says, is more insidious. “It’s the opportunities I was never considered for, because someone assumed I couldn’t handle public speaking or client-facing roles.”

Both men have experienced a subtler, but no less damaging, form of discrimination, often referred to as benevolent ableism. It’s a concept borrowed from Feminist Theory’s benevolent sexism (attitudes and beliefs that may seem positive, but end up reinforcing women’s subordinate status), where protective intent ultimately leads to exclusion.

Unlike overt hostility, benevolent ableism hides behind a facade of kindness and protectiveness. It shows up as unsolicited help, overprotection, exaggerated praise, and decisions made for disabled people rather than with them.

Systemic impact

Attitudes of benevolent ableism have shaped institutions and systems.

“In India, people with disabilities are routinely left out of public spaces, professional opportunities, and leadership roles, not always because of hostility, but because of unspoken doubt,” says Shashank Pandey, a visually impaired lawyer and founder of the Politics and Disability Forum, who has spoken about the harms of benevolent ableism.

For instance, an office may invite job applications from everyone, but if it's located on the 10th floor with no elevator or ramp access, persons with locomotor disabilities are excluded in practice, despite the absence of explicit discrimination.

Similarly, an educational institution might offer a “universal” exam format that heavily relies on visual comprehension, but without provisions like screen readers or scribes, it effectively locks out visually impaired candidates. While institutions are legally obligated to make these provisions available, people with visual impairments have been denied these accommodations. “This isn’t always seen as discrimination,” Shashank notes, “because the system claims neutrality, but in effect, it fails to accommodate.”

The result, he says, is that disabled people are often treated as recipients of charity, not participants in progress. This form of exclusion, cloaked in protectiveness or procedural fairness, is particularly dangerous because it goes unchallenged and yet deeply shapes who gets to belong.

Ankur has experienced this too. His co-workers have sometimes withheld responsibilities or projects from him, assuming that he may not be able to deliver due to his disability.

These stories show that bias is not always loud. Often, it’s what doesn’t happen: the roles people with disabilities aren’t offered, the conversations they are left out of, the assumptions made behind closed doors. Ableism is more damaging when it quietly shapes who is invited, included, or believed capable.

The quiet harm

Sometimes, ableism presents as discomfort, as Anjali Vyas, the founder of the creative advocacy initiative Believe In The Invisible, who lives with multiple sclerosis, has experienced.

A few years ago, during a casual family gathering, she offered her uncle a glass of water. Newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, she was still navigating the emotional terrain of living with a chronic, invisible disability. Her well-educated uncle looked at her and asked hesitantly, “Is it safe for me to take this from you?”

He repeated the concern, a little later, this time about whether his daughter should sit next to Anjali, afraid she might “catch” the illness.

This wasn’t a stranger or a distant acquaintance; this was family. And this wasn’t overt discrimination, but ableism stemming from fear and ignorance. When Anjali’s uncle questioned whether her neurological condition was contagious, even after being told otherwise, she wasn’t just hurt. She felt diminished in a space she had once trusted to be safe.

How can I be an ally?

Allyship begins not with grand gestures but with recognising and challenging these everyday patterns of exclusion. Acknowledging the jokes, the disbelief, the pity, and linguistic othering could be a good place to start.

Phrases like “Are you blind?” or “That’s so lame”, slip casually into everyday conversation. They might seem harmless, but for disabled individuals, they reinforce the idea that disability is synonymous with failure, weakness, or defect.

For Anjali, ableism manifests not only in words but in assumptions. “Because I live with an invisible disability, people often don’t believe I need help or accommodation. They think I’m faking it.” She recounts instances of people downplaying her fatigue or pain with comments like, “Everyone gets tired,” or “At least it’s not cancer.”

Another aspect of ableism, Puneet says, is infantilisation. It’s the assumption that disabled people need to be cared for, spoken to slowly, or managed like children. “Statements like, ‘You’re so brave for doing this!’ may sound like compliments but come from the belief that our lives are inherently tragic or extraordinary.”

“People don’t realise that disability is a dynamic condition. You can walk at some points, and at others, you may not be able to. But the moment you ask for help, say, a wheelchair, you're doubted or questioned,” says Shashank. “Think about the emotional exhaustion that comes with having to constantly justify one’s access needs to strangers, employers, and even friends.”

“You’re so brave!” “It’s amazing how you’re doing this despite your disability.” Comments like these might sound kind, even flattering. But for many disabled people, they feel like thinly veiled pity — a reminder that society still views their lives as inherently tragic, or their basic achievements as exceptional.

Anjali calls it out bluntly: “We are not heroes. If I’m inspiring you, I want to know what you’re doing about it.” She points to how even basic activities, like pouring a glass of water or walking, are praised as heroic feats when performed by a person with a disability. “We become two-year-olds who get applauded for taking their first step. It’s funny, but it’s also sad,” she says.

“Celebrate our achievements in the same way you would for anyone else, not as miracles, but as milestones,” she says.

Ankur echoes this: “I’m not doing anything extraordinary if I’m doing my regular job. If I’m travelling independently, that’s not a big deal. Sighted people do that too.”

What can storytellers do?

Change must begin with how disabled people are represented in stories in the media and everyday life, says Ankur. “Stop treating us like superhumans. We’re not. We’re just human.”

Ask yourself, “Why do you see disability as something to overcome? Disabled people don’t exist to make you feel grateful for your own life. Stop centring the narrative on how ‘inspiring’ we are for simply living or working. It’s patronising.”

Instead, he urges a shift in focus: “See us as professionals, creators, leaders. Advocate for access, not pity. Acknowledge the systemic barriers we’ve navigated.”

For Shashank, breaking stereotypes involves short-, mid-, and long-term strategies. In the short term, meaningful engagement between disabled and non-disabled individuals is key. “Start with a low-hanging fruit. Talk to people with disabilities you know. Don’t assume, don’t avoid.”

“Disability is not exclusive. It is something almost everyone will experience in their lifetime, due to age, illness, or injury”, Shashank says. Accessibility features like ramps don’t just serve disabled people. They help children, elders, and delivery workers. Inclusion benefits everyone.

Anugya Srivastava is a communications professional who is passionate about disability, media and its intersections.

Edited by Priti Salian

Media recommendations

Read

Filmmakers are rewriting the script on inclusion

I loved this interview of filmmakers Pavitra Chalam and Akshay Shankar of Curley Street Media by Pulakita Mayekar for Godrej DEI Lab. Pavitra and Akshay share their journey in inclusive storytelling and good media representation of people with disabilities. So many things in the interview caught my attention.

On avoiding the ‘able-bodied gaze’ in their visual and narrative choices:

“We don’t arrive with a script. We arrive with curiosity, humility, and time. The time part is key. From a production budget perspective, we would rather sacrifice expensive camera equipment in favour of an extra day with our heroes.

Our creative vision is shaped by every interaction—every conversation around a kitchen table, every glance exchanged behind the camera, every quiet truth shared off-the-record.

We let our films be shaped by surprise, by consent, by collaboration.”

On structural changes required in the Indian documentary space to enable more self-representation and authorship by storytellers with disabilities themselves:

“We often hear talk of “giving voice” to storytellers with disabilities, but that framing itself is flawed. People with disabilities already have voice. What’s missing is a system that’s quiet enough to listen. One that isn’t built on gatekeeping, but on shared authorship. One that doesn’t just open the door but questions who built the door in the first place, and for whom.”

Watch

Disability affairs reporter Nas Campanella’s piece for ABC News nicely breaks down the social model of disability:

Listen

I recently had the honour of being interviewed by Qudsiya Naqui for her podcast Down to the Struts. Qudsiya has interviewed so many incredible people working in the realm of disability inclusion across the world, so when she invited me to her podcast, I was truly humbled. Do give it a listen if you have the time!

Opportunity

Apply to Beyond Ability, a dedicated mentorship program led by Abhishek Anicca by South Asia Speaks, designed to empower disabled writers across South Asia. This initiative offers personalised guidance to writers navigating the unique challenges of disability, fostering a supportive environment for their creative endeavours.

Applicants may choose to apply in one of the following areas: Fiction, Non-fiction or Poetry.

Deadline: 30th September 2025

Thanks for reading today’s issue. As always, share your thoughts by hitting reply or engaging with me on LinkedIn and Instagram. Reframing Disability has an Instagram account too - follow and engage!

Warmly,

Priti

Priti, I've been reading your newsletter for quite awhile now and I am always impressed at the well-considered writing and insights. My disability is non-apparent and as someone who only learned I had a disability about 10 years ago, I still struggle to know what I need to succeed in a society not built for neurodivergent people, let alone those with physical disabilities. I especially appreciated Nas Campanella’s piece that you shared. I've written about universal design (https://jodihausen.substack.com/p/whats-the-curb-cut-effect) and never miss the opportunity to remind people that we can change the paradigm. We just need to make the rest of the world more cognizant. So good on you for your work here and with the StoryLab mentorships. Please keep it up!

I feel very tired constantly battling abled gaze and narratives within my environment and with strangers. I really appreciate when I witness articles like these.