Hello! How have you been? I have some terrific news to share with you! Reframing Disability is now collaborating with other outlets to publish original work and to republish content for a wider reach.

The collaboration with White Print, India’s pioneering English language lifestyle magazine in braille, is particularly meaningful to me. Founded by Upasana Makati, White Print has been published consistently every month for 11 years. I had interviewed Upasana for Pacific Standard many years ago, so when she reached out with a request to republish a piece from Reframing Disability, I didn’t think twice. What could be better for a newsletter on disability inclusion than reaching 10,000 braille readers in India? Now you can read Aditi Gangrade’s interview published in Issue Twelve of Reframing Disability and in (Volume 11- Issue 4) of White Print in braille, available at libraries near you.

Close to my heart is the collaboration with Disability Justice Project, an American initiative training disability rights defenders in the Global South in rights-based storytelling. I’m part of the DJP team and trained the latest cohort from Nepal.

When I asked Jody Santos, the founder of Disability Justice Project, if I could republish a story I contributed to the website, she happily agreed. Thank you, Jody!

Would you like to collaborate with Reframing Disability to co-publish or republish content in various accessible formats? Just hit reply - let’s chat!

In this issue, find my article on the accessibility of Indian elections, key points I considered for fair and inclusive rights-based reporting, media recommendations, and opportunities.

My story on the flaws in the accessibility of the Indian voting process was published last week by the Disability Justice Project. It’s an example of the rights-based approach I follow for every story about human rights violations. Election accessibility may seem to many like a “special arrangement” for persons with disabilities. However, failing to provide it violates the fundamental right to vote, a right every citizen in a democracy is entitled to.

Read the republished piece below and don’t miss the reporting tips which follow. If you prefer text-to-speech to listen to the article, find it on DJP’s website.

Democracy Denied

Disabled Voters Face Barriers in India’s Polling Process

This is the second report in DJP’s series on voter accessibility in 2024, a year when a record number of voters will head to the polls, with at least 64 countries, representing about half the global population, holding national elections. The first report will take you to Rwanda, where a disability movement led to the electoral inclusion of persons with psychosocial disabilities.

Priya Srivastava is an independent young woman based in Lucknow, North India. During a recent state election, sitting in her wheelchair, she was unable to reach the button she wanted to press on the electronic voting machine (EVM). The machine was placed higher than the recommended height for accessibility to wheelchair users. Srivastava opted not to seek assistance from anyone in the interest of her voting privacy and independence. She pressed the button she could reach, which was for another candidate from another political party. “I made my choice based on accessibility,” Srivastava says.

EVM access is just one of the barriers to voting for people with disabilities in India – and not just for wheelchair users but blind people, too. To vote independently, blind Braille users refer to the Braille ballot sheets available at polling booths for the names and party symbols of the candidates. This information should be in the same order as on the EVM, to enable a blind person to easily locate the candidate on the EVM. “Sometimes, when the Braille ballot sheets and the EVM don’t follow the same order, EVMs become inaccessible to us blind users,” says Divya Pandey, who lives in the central Indian city of Bhilai.

In Lucknow, Priya Srivastava found herself unable to reach the electronic voting machine during a state election, forcing her to vote for a candidate she didn’t choose. Photo courtesy, Priya Srivastava

General elections in India are being conducted in seven phases, having started on April 19 and ending on June 1. Among the close to a billion registered voters, nine million are persons with disabilities. And unsurprisingly, disabled people still can’t participate in the electoral process independently in the world’s largest democracy.

To protect the rights of disabled people, India has a progressive Rights of Persons With Disabilities (RPwD) Act, 2016. It follows the principles of the international human rights treaty, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities(CRPD). The RPwD Act specifically states that the “Election Commission of India (ECI) and the State Election Commissions shall ensure that all polling stations are accessible to persons with disabilities and all materials related to the electoral process are easily understandable by and accessible to them.”

The constitutional body responsible for conducting free and fair elections, the ECI, started taking steps towards equal access for voters with disabilities almost two decades ago. After disability activist Javed Abidi filed a petition at the Supreme Court in 2004, the ECI was directed to take measures to ensure the accessibility of the general election later in the year. Wooden ramps at polling stations, Braille on the EVM, separate queues for disabled people and training for polling booth officers were some of the features introduced.

More thorough guidelines for accessible polling and voter awareness strategies were framed before the 2019 general elections. They include important features like situating all polling stations on the ground floor and the provision of ramps with proper gradients. In the same year, postal ballots for people with disabilities were introduced, so that people who couldn’t get to the polls could vote from home. Late last year, guidelines mandating the use of disability-sensitive language by political parties and their representatives in their campaigns were also released. These guidelines require that any references to disability or people with disabilities should not portray them as incapable or perpetuate prejudices.

“It’s inspiring to see progress towards inclusivity, though there’s still significant ground to cover, ” said Arman Ali, executive director of the National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People (NCPEDP), in a recent LinkedIn post. Ali has worked relentlessly for the political inclusion of disabled people in India. But, as he acknowledges, there are still gaps in the implementation of accessibility, even with a fairly strong legal framework and guidelines.

Barriers to voting are one reason why many persons with disabilities in India don’t even register to vote.

There’s a huge gap in the registration and enrollment of disabled voters. The 2011 Census recorded 18,950,358 persons with disabilities over 19 years of age in India. For the current election, only 9,007,755 are registered in the electoral rolls, meaning over half of all persons with disabilities in India are still not casting their vote.

A lack of awareness about the electoral process is another reason for the lower registration of disabled voters. “Targeted accessible campaigns and awareness about the electoral process are needed to encourage disabled people to vote,” says accessibility consultant Manav Goel, who lives in Bahadurgarh, near Delhi.

Inaccessible Infrastructure

Even if more disabled people did register to vote, they’d face significant challenges actually doing so. The majority of India’s 1.5 million polling booths are situated in schools, colleges, or community centers, where infrastructural accessibility is crucial but nonexistent. How can election accessibility be achieved seamlessly if the infrastructure in a country is not accessible?

Per the RPwD Act, both public transport and infrastructure were supposed to be retrofitted for accessibility by June 2022. Due to delays, the deadline was revised to March 2024. However, according to a September 2023 audit by India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment, less than 20% of the work on public buildings in the funded states and union territories has been completed.

Across the country during this year’s elections, accessibility in polling booths is being integrated at the last minute. Temporary wooden ramps, sometimes plywood planks, are placed at the entrance of polling booths without measuring their gradient. In a booth in South Bengaluru, a voter said that a plywood plank was being placed only when a wheelchair user arrived to cast their ballot.

“So often, I find ramps covering the entrance, and then one or two steps to enter the polling room,” says Smitha Sadasivan, a member of Disability Rights Alliance (DRA) based in Tamil Nadu in southern India. DRA is a coalition of independent, community-based advocacy organizations. In April, on polling day in Chennai, Tamil Nadu’s capital, Sadasivan was working as part of the district election office’s access audit team. She found the ramps so steep that she couldn’t go up without someone pushing her wheelchair. “This shows the lack of clarity on accessibility and accessibility standards among the authorities,” she says.

“All across India, the perception of having made a place accessible is to put a decent ramp at the entrance and some form of quasi-accessible toilet,” says Vaishnavi Jayakumar, also a DRA member. The ECI building itself has no ramps for steps beyond the entrance, she adds.

Srivastava from Lucknow says that often the space between the wall and the EVM isn’t enough for her wheelchair to fit easily. This election, she was unable to cast her vote independently because of this reason.

“It’s not about elections per se,” adds Jayakumar. “The bigger question is why are schools and colleges not accessible yet.”

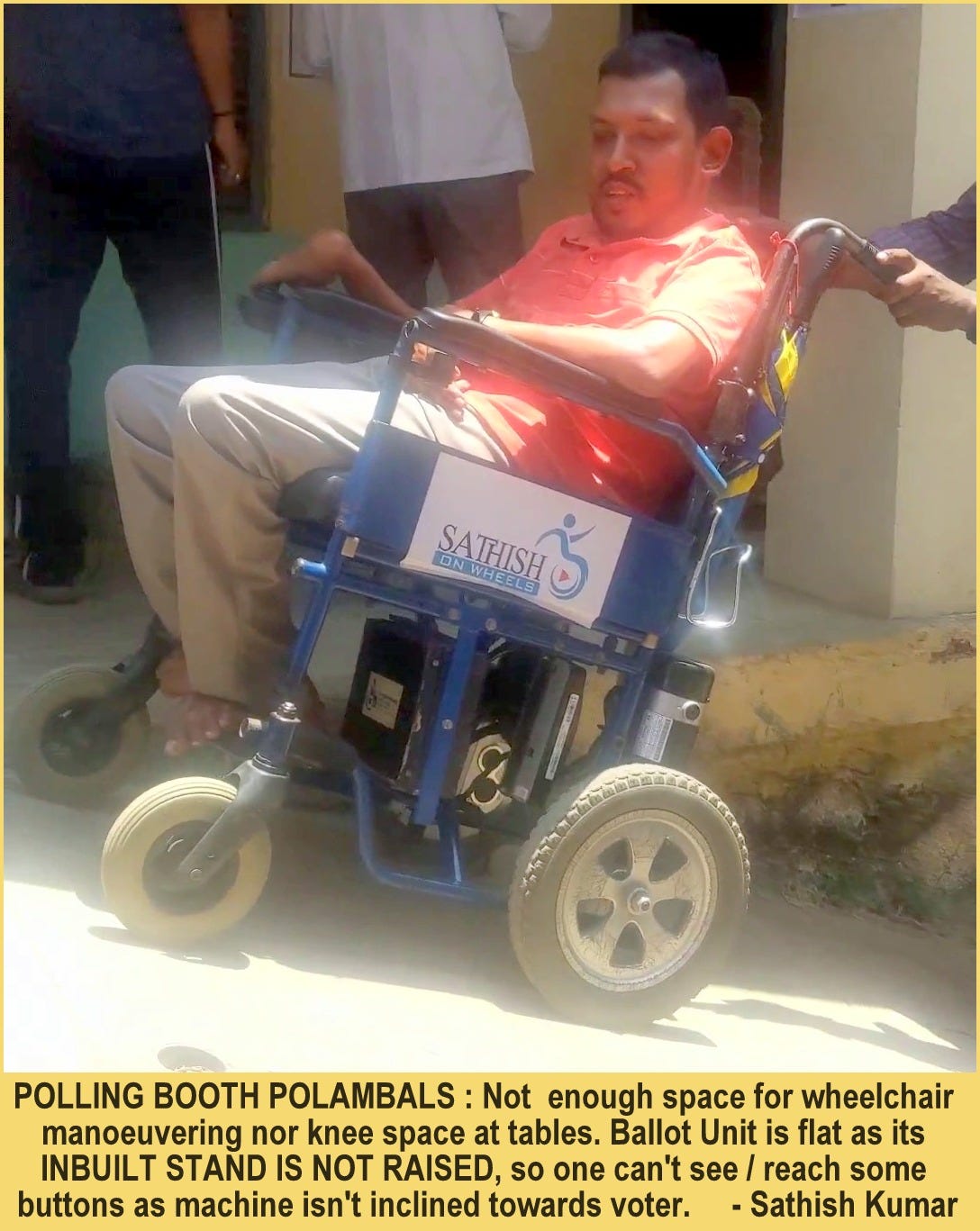

Sathish Kumar of DRA navigates a steep ramp outside a polling booth in Tamil Nadu. Photo courtesy DRA.

The accessibility of India’s public transport is not something to boast about either. According to a September 2023 audit by India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment, only 6% of public transport buses are fully accessible, while 29% have partial accessibility. To facilitate commuting to the polling stations, accessible transport is a government provision for disabled people. Requests are taken through the 1950 helpline for voters or the Saksham mobile app, meant specifically for voters with disabilities. However, the Saksham app itself is not fully accessible to blind users, according to blind accessibility tester Amar Jain.

“Some e-rickshaws provided as accessible transport do not have ramps, so are not useful for wheelchair users,” says Delhi-based Dr. Nonita Gangwani. Being tall, Gangwani also faces challenges fitting into some accessible cabs with her wheelchair.

Priority queuing is another provision at polling booths for persons with disabilities and seniors. However, in many booths, this feature is either not offered or lacking proper signage. Goel says that his polling booth once had bamboo barricades separating queues. These barricades made the line too narrow for his wheelchair, thus preventing him from accessing the priority queue.

Missing Postal Ballots for Absentee Voters and Challenges for Disabled Polling Officials

Voting from home is a valuable facility, but a number of people haven’t received their postal ballots for the current election. Dr. Deepa V from Kodagu in South India is one of them. “I didn’t want to travel to my home city to vote, so being a person with a disability, I applied for a postal ballot, but it never arrived,” she says. “I lost my chance to cast my vote this year.”

Deepa, who walks with the support of calipers, had volunteered to be a polling booth official for the 2023 state election, but this time she declined. “For people with disabilities, volunteering for election duties is a labyrinth of challenges,” she says.

For example, presiding officers need to make the journey from the booth to the mustering center (the venue from where EVMs and other polling paraphernalia are collected by polling officials) to collect the EVMs. This trip can be a logistical nightmare if the terrain is bad and the ride is cramped and jerky. “The mustering center I visited had a steep ramp with no railing, so I couldn’t enter the center,” Deepa says.

Staying overnight also can be challenging for physically disabled people if the accommodations provided to the presiding officer at the polling station don’t include accessible toilets. “We need to bring attention to this issue, or persons with disabilities wouldn’t want to offer their time for election duties,” Deepa says.

Excluding Marginalized Groups

One thing that grossly lacks attention and effort from the government’s side is the inclusion of marginalized groups such as homeless people, those in care homes, and mental health institutions.

The Representation of the People Act, 1950 disqualifies someone from voting only if the person is of “unsound mind and stands so declared by a competent court.”

However, there are cases of people with intellectual, learning and psychosocial disabilities from institutions, care homes and organizations being stopped from enrolling as voters, says Jayakumar. She has worked actively for their inclusion in the elections in the past.

“A written clarification from the ECI is needed mentioning that people with learning, intellectual and psychosocial disabilities have the constitutional right to vote,” Jayakumar says.

This clarification should be published online and included in the compendium of instructions. “Given that their voting rights are enshrined by the constitution, such a circular would be useful to get enrollment done without unpleasantness,” she says. “Voting enrollment should also happen in a systematic way all year round instead of just before the elections.”

Overall, to streamline accessibility, experts emphasize strengthening the voting system with periodic capacity building and educating officials and personnel involved in all segments of the electoral process. “The committees and the officers enrolled for accessible elections at the district, state and national levels should be strengthened to enforce implementation of the strategic framework of implementing accessibility and monitoring the same,” says Sadasivan. “An active involvement of persons with disabilities throughout the process is critical.”

Disability Rights Alliance regularly tweets about election accessibility in India as #Votability.

Reporting considerations for this piece

Key points that helped me take the rights-based approach.

It meant establishing that failing to provide accessibility is a violation of the fundamental/human rights of a person with a disability.

Data about disability How many persons with disabilities live in India? How many of them are over 18, the voting age? How many are enrolled as voters? This helped me establish evidence and dig into the reasons why not every disabled person might be casting their vote.

The legal framework Which international frameworks does India follow and if the Indian laws align with them. Does India’s Disability Law (RPwD Act of 2016) have any rules for accessibility in the elections?

Accessibility guidelines by the Election Commission of India One of the most important things in this story was to find the latest accessibility guidelines and check what is not being followed appropriately (almost everything!). I made a note of which guidelines were meant for which disability. This helped me understand the access needs of people with different disabilities. Now I knew who to approach for an interview and the questions to frame for my interviewees.

Other things that supported my reporting

Important lessons One of the big lessons for me while working on this story was that if more time and deliberation were put into the work on accessibility, and everything wasn’t last-minute, the job wouldn’t be so sloppy. Another one was that election inaccessibility is actually rooted in the bigger issue of inaccessible infrastructure, particularly in educational institutions where polling booths are stationed. Both these lessons guided the flow of the story.

Gleaning social media for tips Since early this year, I have been keeping an eye on the news and social media for any work being done on election accessibility and the complaints and demands of disabled people. As I came across information on socials and WhatsApp groups, I collected it in a document for later use. A webinar I attended was helpful in shining a light on the role of caregivers in voting.

Finding support in networks Being part of several supportive disability networks helped me find interviewees for this story.

Covering missing perspectives Indian reports haven’t looked into the issue of accessibility for polling officers with disabilities or the voting rights of persons with intellectual, learning and psychosocial disabilities. I covered that in this piece.

Although there was an initial surge in coverage about voting accessibility this year, it dwindled after a flurry of reports before and during the early days of the election. More rights-based coverage is needed in India and an understanding of disability rights as human rights. Otherwise, we will continue to read headlines such as, “Differently abled, same passion for democracy” in mainstream newspapers. Can anyone enlighten me why disabled people are not expected to have the same passion for democracy?

Accessibility Tip Of The Fortnight

Do you switch on captions when you set up a Zoom meeting? It can be done by only the host while setting up a meeting, not later.

Here’s why you should

Deaf or hard of hearing people, or those who have trouble processing spoken words need this service to be able to participate in the meeting. It also helps those who cannot follow the speaker’s accent, or get distracted while listening. Participants taking notes find captions quite helpful when they miss words.

What you can do

Turn on “Automated Captions” and “Full Transcript” settings in Zoom. Also turn on “Save Captions” so your attendees can save the transcript themselves to refer to later. It’s like providing a written record of the meeting.

Recommendations

Alt Text Guide

My friend, journalist Johny Cassidy’s initiative, the BBC’s guide for writing alt text descriptions on all kinds of images, is out. Be it decorative, informative, functional, complex, charts, maps, illustrations, and text-heavy images, you’ll find all your text alternative answers here. Read Johny’s interview in Reframing Disability’s seventh issue about his work on accessibility at the BBC.

Participate

In the webinar, "The roadmap to accessibility maturity: TIAA's journey, “guest speaker Gina Bhawalkar, principal analyst at Forrester, will share the latest trends and data in the digital accessibility space. Lesley Hanlin, head of accessibility and inclusion at TIAA, will share the steps she took to build, grow, and mature their accessibility program.”

Date: Thursday, 13th June 2024

Time: 12 pm to 1 pm EDT

Watch

This Indian folk music video found a unique way of including sign language accessibility. The lead signer Kartik (in a black shirt) is a deaf music interpreter. Thanks, Pallavi Kulshreshtha for the tip!

Read

Ever heard of “alt-text selfies”? I hadn’t either! I recently came across this project which describes itself ‘as a celebration and collection of alt text selfies’. These are selfies “approached from a disability lens” and written by disabled people. Unlike other selfies and self-descriptions that are often visually focused, these poetic alt-text selfies “might focus on feelings, smells, tastes, sounds, emotions, textures, or some combination” in a sentence or a paragraph. A must-read!

Opportunities

Disability Data Fellowship by Belongg and Mission Accessibility

For: Indians who can work with datasets (refer to the document for more info)

Duration: 3 months

Compensation: 50,000 INR per month

Application deadline: 14th June

We can work storytelling competition

For: Disabled storytellers between the ages of 18 and 35 from Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Senegal, Ghana, or Nigeria

Storytelling formats accepted: writing, audio production, videography, visual artistry, or photography.

Application Deadline: June 28, 2024.

Thanks for reading this issue of Reframing Disability! Reply to this email with your thoughts on today’s content and connect with me on LinkedIn and Twitter! Share Reframing Disability widely to support my work. You’ll find me in your inbox again in two weeks. Until then, stay safe and healthy!

Warmly,

Priti